What it Means to Have the Privilege of History in Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things

By McKenzie Twine

Arundhati Roy

The privilege of history is a common issue that arises in colonized countries like India. To hold on to and create personal history is something many people in colonized countries are unable to do as part of colonization is adapting the culture and practices of the colonized to meet the standards of the colonizers. The public goal of colonizers is to civilize and bring religion to colonized people, not that colonization is a very civil practice; however, the true benefit for the colonizers comes from all of the resources that they can steal from infiltrated countries. Arundhati Roy’s novel The God of Small Things follows twins, Estha and Rahel, as they grapple with the consequences of their cousin Sophie Mol’s accidental drowning. As a result, the twins are hounded by history. They become increasingly aware of the lack of control they, and everyone around them, have over their fate. In an interview with Taisha Abraham, Roy says her novel is about human nature. Roy discusses how human society likes to create divisions, and fight wars, and find love across these divisions (Abraham 91). The three most prevalent divisions in Roy’s novel are the divisions between British and Indian, higher and lower castes, and men and women. Each of these divisions is strongly rooted in Indian history, but they also adapt to British influence once the country is colonized. One of the most thought-provoking results of these divisions is how they serve to diminish the history of the oppressed and further the effect of colonization. In Roy’s novel, Indian history is diminished because the characters have lost connection to their ancestors and experienced trauma at the hands of the British; the caste system is used to force a large portion of the population into a subservient position, and women are denied the ability to exist outside of patriarchal expectations.

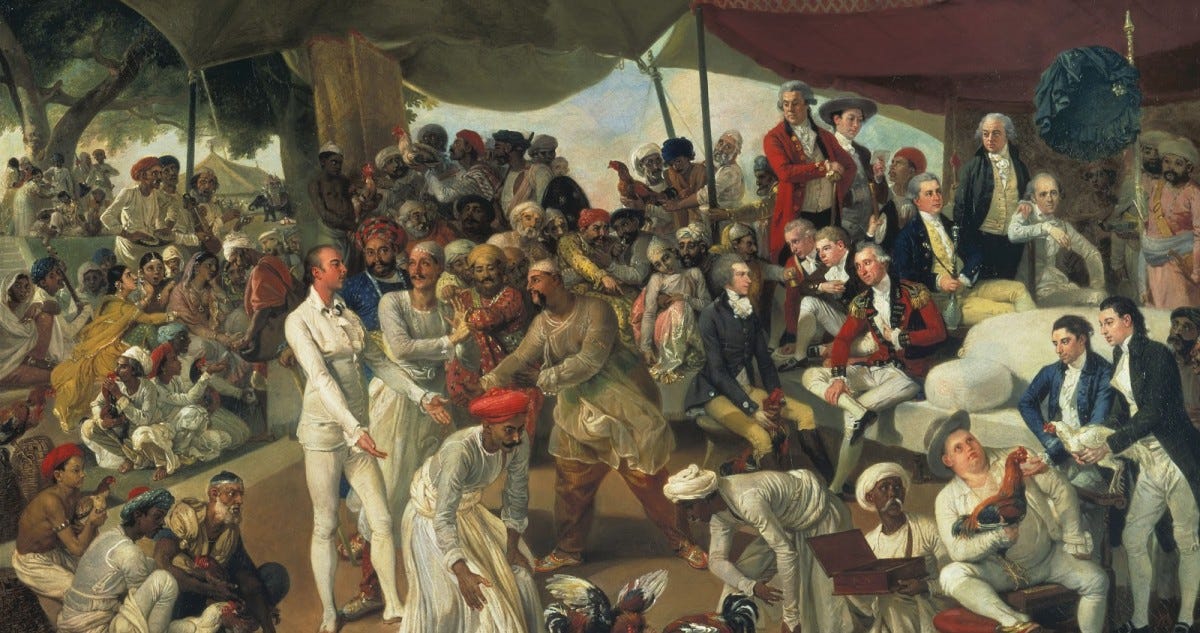

While colonization is not a topic that is often explicitly discussed in Roy’s novel, the effects of British colonization continue to ripple through the lives of each of the characters. Chacko, the twin’s uncle, tells them, “They were a family of Anglophiles. Pointed in the wrong direction, trapped outside of their history and unable to retrace their steps because their footprints had been swept away” (Roy 51). Not only is Chacko referring to India’s culture being overtaken by British culture, but he is also referring to their lost ancestral history, which disappeared when they embraced and adapted to the colonizer’s history. Their history has been stripped down, first by colonization, and then more recently by India to attract tourists. The History House, the place where Velutha is violently beaten during the twin’s youth, has now been transformed into a hotel. It “[becomes] the centerpiece of an elaborate complex, crisscrossed with artificial canals and connecting bridges,” and it is “surrounded by smaller, older, wooden houses — ancestral homes — that the hotel chain had bought from old families” (Roy 120). All of the history associated with the house is condensed into “Toy Histories for rich tourists to play in” (Roy 120).

The History House, and its purpose in the novel, is heavily symbolic of colonialism in India. There is a distinction in the novel between the physical location of the History House, which is where the twins are present for Velutha’s beating, and the metaphorical location of the History House, which arises when Chacko refers to their ancestral history as an old house, one where they must go inside and look at the contents of the house to fully understand their history. Colonialism took away their ability to venture inside the metaphorical house of their history as they have become too disconnected. Paul Jay discusses this relationship in his article stating, “In making the History House both the representative site of British colonial terror and the site of the family’s personal terror, Roy explicitly links the ‘big things’ and the ‘small things’ in her novel and connects them to the long global history of colonialism in India” (98). The big things are history, and its overarching effect on the people of India, while the small things are the personal things that happen to each character. Both the big and the small things combined result in the erasure of Indian history through colonization.

The Meenachil River

The imposition of British standards upon characters in the novel also causes the characters’ trauma. Trauma, as an aftereffect of colonialism, comes in many forms throughout the novel; the most apparent instances of it are characters feeling rejected by their loved ones. The rejection comes from the character’s inability to meet the unrealistic standards of whiteness. Ammu’s trauma comes in the form of her father’s rejection. After she divorces her abusive husband, who asked her to sleep with his British supervisor, her father dismisses her experience because he does not believe that a British man would ever want to sleep with another man’s wife. Chacko, Ammu’s brother, is rejected by his white, British wife Margaret Kochamma, despite his prestigious Oxford education. He feels, in part, as if he is unworthy of her because he will never be a British man (Freed 225). Once Estha and Rahel meet their cousin Sophie Mol, they begin to realize that they will never be seen as equal to her in the eyes of their older family members. Kochu Maria refers to Sophie Mol as an angel, and there is the implication that this is because Sophie Mol is white. In the novel, it says, “Littleangels were beach-colored and wore bell-bottoms,” while “Littledemons were mudbrown in Airport-Fairy frocks with forehead bumps that might turn into horns” (Roy 170). While all of these characters experience great trauma as the result of British ideologies, no character experiences greater trauma than Velutha who is beaten for the mere insinuation that he had any involvement in Sophie Mol’s death and the alleged assault of Ammu, a woman from a higher caste. Neither accusation is true, but the authorities are so emboldened by their higher social status that they do not feel the need to prove the claims before they beat him to near death. To them, Velutha is a lower-class citizen, which makes him inherently guilty.

Before British interference, the caste system was predominantly one of both religious and social implications. The religious aspects of the caste system were deeply tied to Hinduism and the belief in reincarnation. When a person was reincarnated into a lower caste, it signified that they had committed an act in their past life worthy of punishment in their current life. Being born in a higher caste signified the opposite, and those people must have lived an exemplary past life to receive such a powerful reward. Social implications arose from the lack of mobility between castes, as the caste a person was born into was the one that they would also die in. There was only one way to achieve any sort of social mobility, and that was to live an exemplary life and hope that those actions would be enough to result in reincarnation into a higher caste.

Caste only became a civil system of interpersonal relationships sometime between 1829 and 1858: during which time, the British declared caste would no longer be associated with Hinduism (Dirks 132). Without the religious aspects of caste, it became easier to politicize the system. The British decided to remove the caste system from Hinduism because they believed Indians were more connected to the caste system than they were to their religion. Nicholas B. Dirks provides an insight into the British opinion on the subject stating, “the fear of loss of caste dissuaded potential converts from abandoning Hindu practice more than any other doctrinal consideration” (131). One of the main goals, as it often is with colonization, is to convert the colonized to the religion of the colonizer. There was also some level of recognition that caste functioned as a system of oppression; however, the British believed that with caste separated from Hinduism, the system would improve (Dirks 133). The hope was that caste would not be used by the government as an excuse to deny jobs, education, and equal treatment to others, but, as Roy’s novel demonstrates, this is not the case.

Though the caste system did not technically still exist in the timeline of Roy’s novel, the attitudes of many characters toward those in other castes shaped the history of Paravans and those in higher castes. Velutha is described as a “Paravan with a future” (Roy 112). He can go to school, learn a trade, and build strong relationships with people in higher castes. His education allows him to diverge from the typical jobs Paravans have in Indian society. The caste system makes it easy to force all of the hard labor on the lower castes. As Ajay Sekher says, “The working people were eternally subjugated and victimized and their hard labor exploited to torture themselves by this brutal system of social engineering. … Nothing but lifelong slavery and subhuman fidelity is expected and allowed in this system” (3446). The caste system perverts the ties between interpersonal relationships so extensively that the older characters in the lower castes feel obligated to report anyone who dares to venture outside of the pre-established system. This fidelity is why Vellya Paapen, Velutha’s father, decides to tell Ammu’s family of her and Velutha’s affair; he is ashamed of his son’s actions.

During the novel, the caste system has become flexible enough that Velutha can move outside of his caste when it comes to his jobs; however, he cannot do so when it comes to his love life, nor is he capable of leaving a significant mark on the world. After Sophie Mol arrives, Velutha begins an affair with Ammu. They never notice each other before that moment because he is supposed to be socially inferior to her. This connection is one of the key events that lead to Velutha’s death. In the caste system, there are love laws; Velutha and Ammu break these laws. There are also rules about who and what those in the lower castes can touch. These laws are part of what adds to the scandal of Velutha and Ammu’s relationship, as he is not supposed to touch Ammu because he is untouchable, while she is touchable. There are many references in the novel to the rules of the caste system before it became an illegal practice. One of the most prevalent laws, outside of the love laws, is that Paravans once had to crawl backwards to sweep away their footprints so the touchables would not have to touch the ground the untouchables walked on. Despite this practice being defunct when the novel takes place, Velutha is never able to leave any mark of his existence behind. His status as a Paravan causes his presence and all of his accomplishments to be overlooked. Estha and Rahel’s family also ignore Velutha’s impact on their lives as it would bring them shame to acknowledge Velutha and Ammu’s affair, and the lies they tell to cover it up. After Sophie Mol’s death, Margaret Kochamma never thinks of Velutha as “He left no footprints in sand, no ripples in water, no image in mirrors” (Roy 250). Margaret Kochamma has no recollection of the man accused of killing her daughter because she is never told of the mistakes made by the police. If Velutha’s existence and pain were remembered, the recognition would call into question the efficacy of regulating caste relationships and the barbaric treatment of those in lower castes.

Women’s roles in Indian society also affect their ability to have a history of their own making. Early in the novel, it is revealed that Ammu is divorced from her husband, and that is why she has moved back home. As a result, Ammu has to decide which last name she would prefer to use after her divorce. She has two options, and neither option appeals to her. One, she could keep her abusive husband’s last name; two, she could switch back to her abusive father’s last name. Estha and Rahel seem to be very aware of the internal struggle their mother goes through. The children have exercise notebooks that they write in and, “On the front of the book, Estha had rubbed out his surname with spit, and taken half the paper with it. Over the whole mess, he had written in pencil Un-known. Esthappen Unknown” (149). Without a last name, the twins and Ammu have no way to pull on their history. Last names help identify where you come from and who your family is, but Ammu is not sure she wants to claim either family. There are also instances in the novel where Rahel is only remembered based on her male relatives; even her mother’s scandal is swept under the rug so sufficiently that when Comrade Pillai introduces Rahel to someone she has never met, she is only known through the mention of her male ancestor, John Ipe.

Ammu’s divorce further serves to deprive her of any property of her own or any financial resources. After Ammu’s affair is discovered and Sophie Mol is found dead, Chacko forces Ammu to leave her family home, and her only support system, and never come back. Estha is sent to live with his father, and Rahel continues to live with Mammachi and Baby Kochamma. Ammu’s banishment is what results in her death. She is left alone with no one to watch out for her and no money to put toward her needs. Rose Casey’s article begins with a summary of Indian property law, and how prior to 2013, women had no economic protections in divorce. In the time of The God of Small Things, which takes place between 1969 and 1992, women had no laws to protect them during divorces, and they would not gain the ability to even inherit family property until 2005 (Casey 381). There is also a distinct relationship between Indian property law and British property law as “The gendered dictates of Indian property law grew particularly pronounced during the nineteenth century, during which time colonial British law colluded with Indian patriarchies to further delimit women’s already minimal property rights” (Casey 381). Women in India, no matter their caste, were subject to oppression, but with the implementation of British rule, women were further tied to men. Ammu is an example of what happens to a woman from a well-off family who decides to make her own path regardless of her family’s expectations. She is ultimately unable to make any significant changes to her life as her only bodily freedom comes at the cost of her economic freedom.

It should be noted that History has the power to shape the characters of Roy’s novel beyond societal expectations. There are many instances in the novel where History appears to be an all-powerful entity with the ability to manipulate the character’s lives and actions to maintain the social hierarchy. Vellya Paapen is described as History’s deputy after he takes actions that directly contribute to his son’s violent death. Additionally, History affects the way Ammu and Velutha view each other before their affair, with their connection described as hidden by history’s blinkers. Estha is also affected by History. He is said to be the one that will “keep the receipt for the dues that Velutha paid” (Roy 190). History’s actions as the enforcer prohibit any of the characters from making significant changes in their lives, which results in the stagnation of character growth. Toward the end of the novel, it is revealed that History is not the omnipotent figure that it appears. In reality, History is the expression of human history and all of the ways human rules serve to oppress others. Humans try to play at being a god, thus controlling what others can and cannot do with their lives. Velutha is heavily affected by the enforcement of History. He is destined to fail because he wants to achieve more in life than his social position allows. Velutha’s potential is squandered by the prejudices of others, not because of who he is as a person.

The complexity of what it means to have the privilege of a history is thoroughly displayed in Roy’s novel. She combines the aftereffects of colonialism with the nuances of the caste system while also touching on the ever-changing rights women have in Indian society. History is constructed by the people with power. Every character in the novel then becomes a victim of human history’s interference. Velutha never has the opportunity to become more than a Paravan in the eyes of society, and no action taken by him would ever break through the oppression laid upon him so thoroughly. Ammu is never able to claim power of her own and moves through life on the whim of the men around her. Neither character had a chance to write their own history. Roy shows that history can only exist, in any significant form, for those who hold a place in the highest levels of the social hierarchy or chose to submit to the expectations of the dominant culture; otherwise, a person’s history is easily swept away as if they never truly existed. The privilege of a history in The God of Small Things is completely intertwined with the privilege of power.

Works Cited

Abraham, Taisha. “An Interview with Arundhati Roy.” Ariel, vol. 29, no. 1, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998, pp. 89–92.

Casey, Rose. “Possessive Politics and Improper Aesthetics: Property Rights and Female Dispossession in Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things.” NOVEL: A Forum on Fiction, vol. 48, no. 3, Duke University Press, 2015, pp. 381–399. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43830065.

Dirks, Nicholas B. Castes of Mind: Colonialism and the Making of Modern India, Princeton University Press, 2001. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/hunter-ebooks/detail.action?docID=776369.

Freed, Joanne Lipson. “The Ethics of Identification: The Global Circulation of Traumatic Narrative in Silko’s Ceremony and Roy’s The God of Small Things.” Comparative Literature Studies, vol. 48, no. 2, Penn State University Press, 2011, pp. 219–240. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/complitstudies.48.2.0219.

Jay, Paul. Global Matters: The Transnational Turn in Literary Studies, Cornell University Press, 2010, pp. 95–117. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7591/j.ctt7z8h0.10.

Roy, Arundhati. The God of Small Things, Random House, 1997.

Sekher, Ajay. “Older than the Church: Christianity and Caste in The God of Small Things.” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 38, no. 33, Economic and Political Weekly, 2003, pp. 3445–3449. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4413900.